Liverpool, Tate Museum, June 15th 2019

After being Keith Haring’s studio manager for over six years, Julia Gruen was entrusted to take the helm and lead the Keith Haring Foundation, which was established by Keith himself in 1989. Following Keith’s insights on how to balance the showcase of his art with the commercialization of his images, Julia ensure that his foundation is self-sustaining and able to keep on providing financial support to HIV organizations –as per Haring’s last wishes.

I was really looking forward to meeting Julia, someone who lived and worked at the side of my favorite artist ever, Keith Haring. I was eager to listen to her stories about the man behind the artist and to learn more about the curation of the exhibit that was going on next door at Tate Museum Liverpool.

Julia Gruen: “We met in a very common way: I was looking for a job and I spotted this ad in a newspaper. It didn’t say Keith Haring, only that they were looking for a studio manager. The preliminary interview was conducted by his gallery, because he was abroad. When I finally met this skinny kid—with his glasses and his eyebrows, sitting at a tiny table with lots of tags and a standing phone in the shape of Mickey Mouse on the top of it—the first thing he said to me was “I don’t know what to ask you.” Keith had never hired anybody before, and he never had anybody working for him that he didn’t already know. But he was doing so many projects outside the gallery that they felt, and Keith agreed, that he needed somebody in his studio to manage things. As we started talking about our own ‘circles’ we suddenly realized that we went to the same clubs and we knew a lot of the same people; we just hadn’t met each other yet. And for a 25-year-old, that seals the deal.”

Julia is an authentic New Yorker through and through. She was raised in a liberal family permeated with art –two things that immediately fascinated Keith, who, on the contrary, left a very conservative, suburban household at the age of 19 to move to New York City; an artist’s Mecca and worldwide hub of the gay community.

Julia Gruen: “It was the crazy 70s and 80s in New York City. There’s no secret about that: we were all on drugs, we all partied. But I can say from having worked pretty much by Keith’s side that, yes, Keith liked to smoke pot. Yes, he liked to do this and that, but somehow he had more level-headed than many of his friends, some of whom had serious drug addictions. Keith had such an optimistic view of the world that for him it was kind of impossible to slip to the dark side of addictions.”

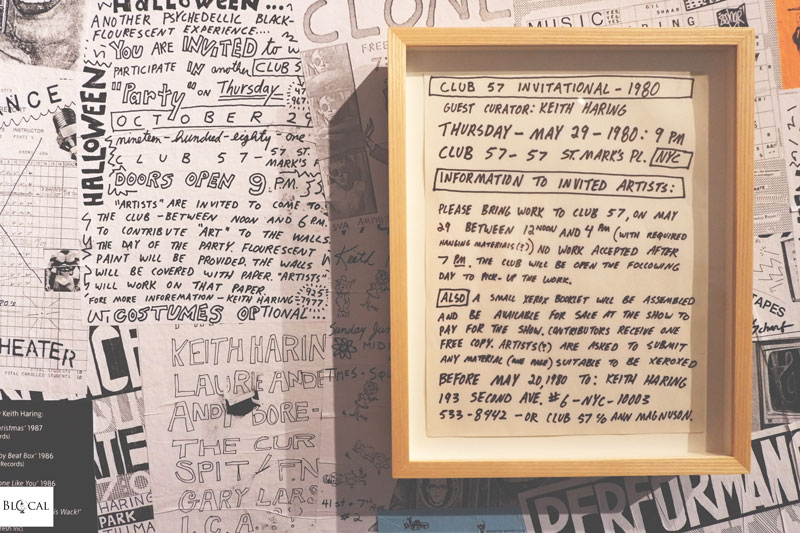

Another characteristic of New York in the 1970s, especially Keith’s New York, was it being populated by aspiring artists—painters, singers, dancers and performers— all in an endless pursuit of The Big Dream. Many of them were friends with Keith; they would go to the same spots in the city and attend the same events, although only Keith had the confidence to go and get what everybody else was simply—albeit passionately— longing for.

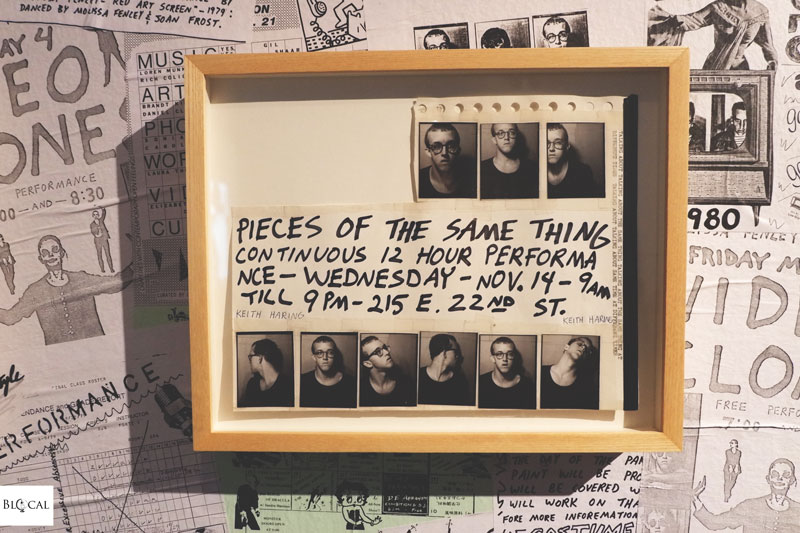

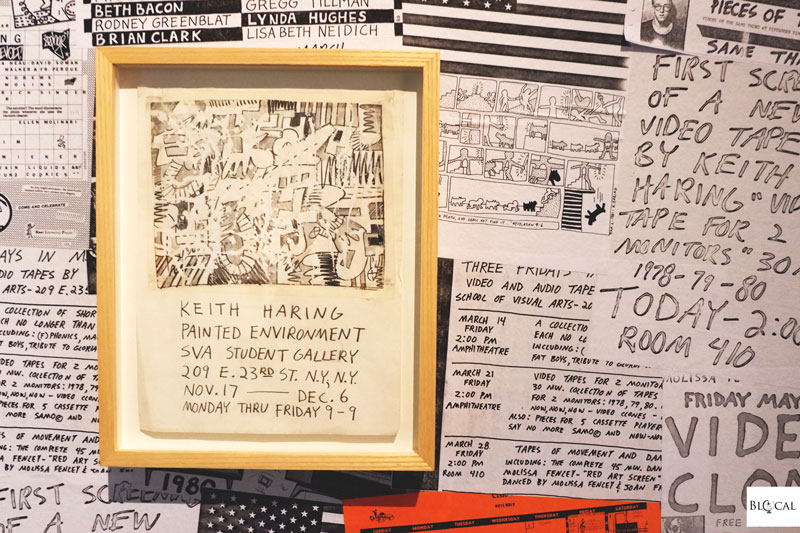

Julia Gruen: “In his journals, especially during his college years—which was when we were all trying to figure things out—he was already very clear on his own evolution as an artist. For example, he would stress the performative aspect of visual art, which is something he deeply cared about.”

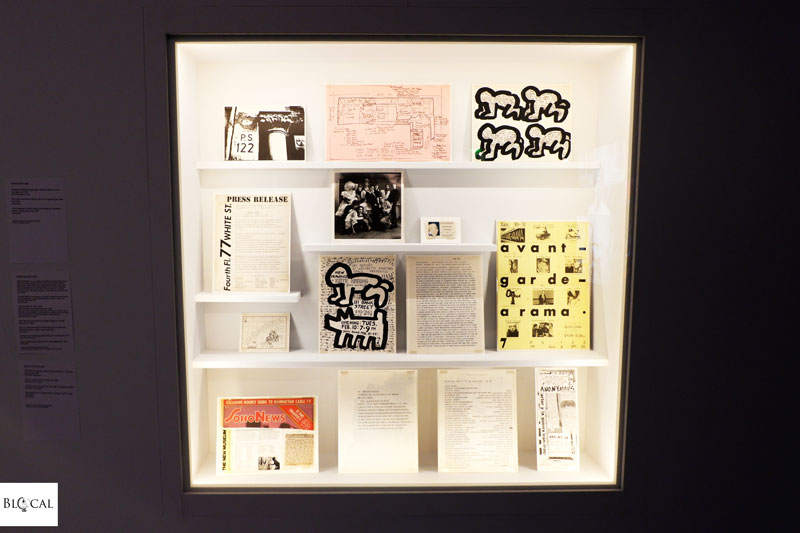

Keith liked to have an audience for his art and considered a piece of art “complete” only if someone else had been there to witness its birth. That’s why he was often drawing in the subways: to connect with a public, because—as he used to say— “The view makes the art”

At that time, the streets of New York were covered with graffiti. Keith was friend of many writers whose names were travelling on trains up and down the city and he had certainly been inspired by the energy of the movement, although it’s incorrect to say that he was part of it. Not only was he not writing his name on behalf of any crew, but first and foremost he was descending into the subway in the daytime, purposely looking to interact with an audience of New York commuters, unlike graffiti artists who were clandestine and avoided the public eye.

Also the medium he used—chalk on paper in the subway or ink and paint in the studio—was very different. Keith had always used the spraycan only as an “accent” and not for full-spray drawings, because he recognized that aerosol wasn’t the medium for him, hence his profound respect for those graffiti artists who could control the medium and create elaborate works of art with it. Keith’s favorite mediums were markers, sumi ink, and paint; only with those could he accomplish the fluidity that is the main characteristic of his work.

Read also: The Keith Haring exhibition at Palazzo Blu in Pisa (2022)

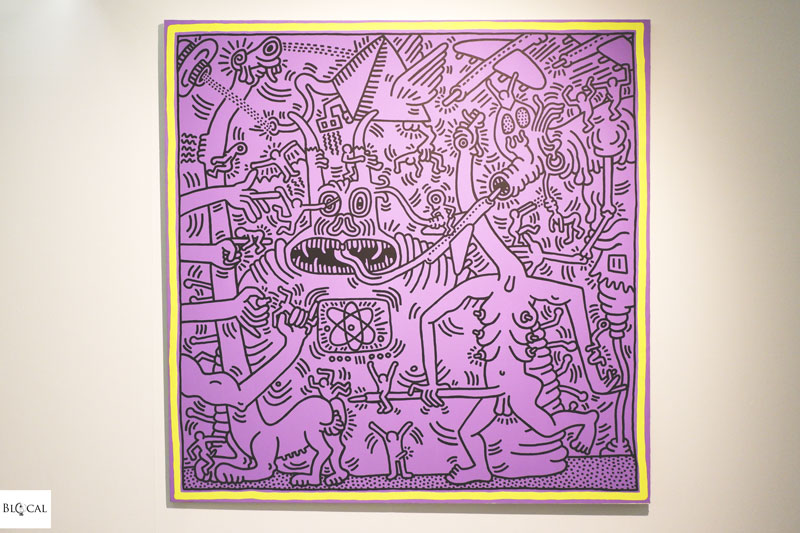

Julia Gruen: “Keith Haring’s works can be mostly identified by his line. Both his peers and today’s artists recognized that his unique talent was that he could visualize exactly what he wanted to create. Even when he was painting these incredibly complex designs on building-sized murals, he would conceive his idea and then he would, he said this himself, “become the vessel.” There is his thought, and it just travels down into his hand and his brush. He could fill spaces of sometimes monumental size without any preparatory sketch or any sort of notes. He just started left and kept going to the right. If the line went in a different way, it was not a mistake: he worked with it. Whatever it was, he didn’t go back, take white paint and start over.”

The fluidity of his line, which I personally only fully understood when I saw videos of him painting himself out of corners (again, performance matters!) was also what allowed him to create his artwork so quickly. Therefore, he chose to only paint on-site. Not only murals, but he would often create the works for a show when he was in that place. Moreover, given his ambivalent feelings toward galleries, he would always also paint a mural for the people living in the city hosting his show. He would talk with his connection or to local authorities to find out where he could paint, preferring poorer neighborhoods or institutions like hospitals and schools. That way Keith painted lots of murals in his later years. One of the most impressive ones is “Tuttomondo,” which he created on the side of a catholic church in Pisa (Italy), breaking all taboos of the time.

Julia Gruen: “It was remarkable. In 1989, an open gay who was diagnosed with AIDS was offered a wall by the priests of a catholic church in Italy. It was pretty spectacular, even though Keith was a very spiritual person. He was raised Lutheran, and he had even been a Jesus freak for a while. However, growing up, he took his position on how the church excluded the gay community and he became pretty much against “organized” religion, as he felt that it was dangerous.”

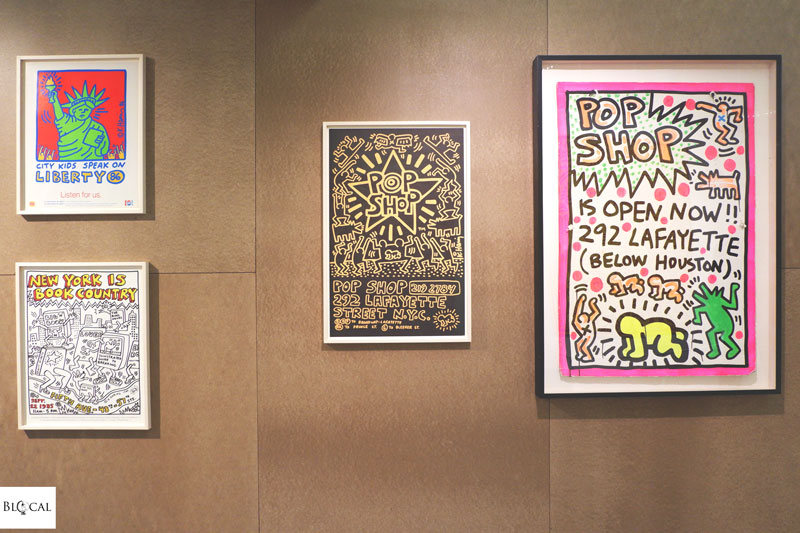

With the same generous spirit that drove him to gift New York’s subways with thousands of drawings from 1980 to 1985 and cities all around the world with beautiful, large-scale murals, in 1986 Keith Haring opened the Pop Shop as a way of placing his work in a more accessible context than an art gallery. The Pop Shop back then was a continuation of his public work. When his paintings and drawings became expensive, Keith wanted to still give back to the people who first supported him—those enthusiastic New York commuters—access to his images.

The Pop Shop was his way of keeping his own feet on the ground and still mingle with his dearest audience by hanging out at the shop every Saturday, often playing incredible music for them.

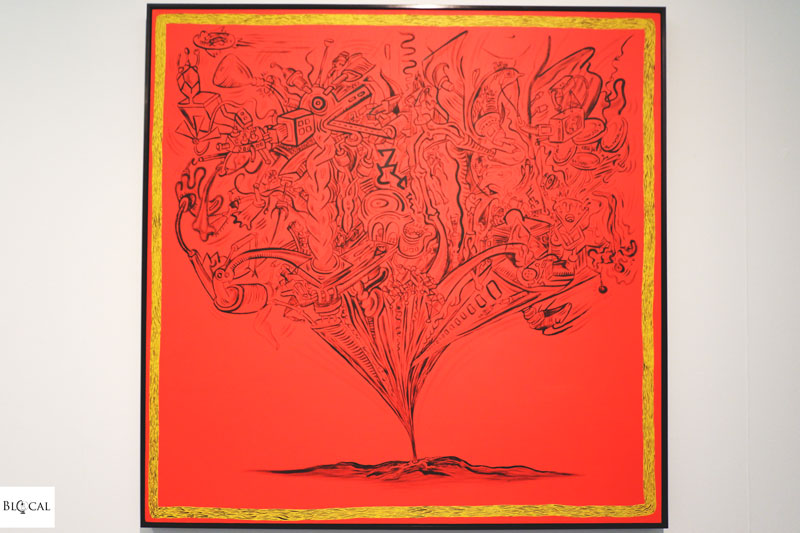

Julia Gruen: “Keith was criticized for the way he spread his work: he was not an elitist, so they said that he was everywhere and his work was too diluted. He was never the darling of the art critics, because he was going his own way, breaking the rules and not doing what he was supposed to. Namely, an artist is supposed to be introduced to the world by a gallery, while Keith simply took his space by himself. Moreover, he was pigeonholed by his own success and his style. He did break up from his style though, and we can see some of these works from 1987 and from 1989 on display here. I especially like these latest works, because they make me wonder what he would be painting today.”

I also was very intrigued by these latest works on display at Tate Liverpool, although my favorite pieces there were the political ones, which I found tremendously contemporary. His campaigns for gay rights—or to be more specific, human rights—are still important today. Keith Haring was a very political artist and a socially conscious person; he protested, and marched, and fought, always fully aware of his social and political impact as an artist. On a more personal level, I’ve always been told how genuine and kind and genuinely “happy” a person he was. And during her speech at Tate Liverpool, his long-time friend, Julia Gruen, simply confirmed this beautiful image I had of him.

Julia Gruen: “Keith was hysterically funny. He was goofy and he loved being silly. Halloween was his favorite holiday: he would always dress up like some crazy thing. He was warm and generous, and he had an eternal optimism. Even after his diagnosis, he just felt that people were intrinsically good. And I’m sorry to say, but I’m one of those cynics. It’s not that I think that all people are bad, but I have got some skepticism. So I learned a lot from Keith; I learned trust, tolerance, kindness and openness. But then, as the years passed, some of that fell away from his persona, because they were such hard times. People were dying every day. We were constantly at memorial services and hospital beds, watching our friends deteriorate. And so, despite his eternal optimism, my most vivid memory is of him in crisis and ultimately dying. I think it takes a long time to be able to return and remember the joy that was there.”

Header photo by Andy Warhol

“Julia”, 1986

(Julia Gruen and Keith Haring)