Dan Witz’s career began in New York City in the late 1970s, when his elaborate street works stood out against the bold, quickly-executed graffiti lettering that was proliferating around him. Since then, his site-specific practice has become a deeply considered exploration of the interplay between artwork, environment, and passerby.

In 1979, Dan Witz was attending art school and playing in a punk band when the graffiti-laden cityscape of New York served as the catalyst for discovering his distinct artistic voice.

“I’ve got this punk-rock spirit in me, you know, and living in New York City back in the late ’70s, it felt like we were at the end of the world. Society seemed to be falling apart at the seams—rich folks getting richer, the poor getting poorer. I was totally caught up in that punk, no-future vibe. But the real game-changer for me was seeing those trains, covered in these massive, beautiful, considered full-length graffiti pieces. When those rolled into the station, it just blew my mind wide open. It was like, wow, I had no idea you could do something like that.”

Dan Witz

Even before the rise of Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat, Dan Witz was already capturing the dynamic essence of New York City’s graffiti culture, creating intricate hummingbird paintings in various urban settings.

“People have been tagging and creating odd art by the roadside for ages. But what I brought to the table was this mix of graffiti vibe, punk-rock soul, and my own twist as a realist painter—not just another guy with a spray can. I’m all about realism in painting. So, I started thinking, how can I blend these three elements to craft something that’s both personal and unique?”

Dan Witz

Beyond pioneering the global street art movement, Dan Witz’s hummingbird series exemplifies his extraordinary focus on detail and ability to craft lifelike depictions that embody the vitality and movement of hummingbirds. These artworks, rendered with impressive precision and realism, can easily be mistaken for living birds at first glance, a testament to Witz’s command of trompe-l’oeil—a technique that fools the eye into perceiving a flat image as three-dimensional.

From the hummingbird series to the “Skateboarders Are Graffiti” series in 2005, which vividly brought skateboarders to life within graffiti landscapes, Witz applied this technique across a range of settings, creating small, easily overlooked masterpieces that required a keen eye to spot.

Witz’s approach to street art is characterized by its capacity to surprise and engage passersby, placing small yet significant works in unnoticed urban spaces. This not only serves as a form of artistic expression but also prompts reflection on the urban environment and the role of art within it. By integrating his work so naturally with its surroundings, Witz invites us to discover beauty in unexpected places, while emphasizing that a wall is not merely a canvas but a crucial part of the artwork’s context, influencing its perception.

This way, Dan Witz encourages observers to appreciate the hidden beauty in the city’s chaos, thereby enhancing the interaction between art, viewer, and environment.

His work is a reminder that art can exist and be appreciated beyond conventional spaces, and this is just one facet of the “street art ethos” he introduced to the art world—a concept of romantic engagement with public space that, regrettably, has disappeared over the decades.

“I kept it all under wraps, really private and secret. I didn’t want to ‘sell out’ or anything like that—it just went against everything punk-rock stood for. My street art had to be anonymous and free, not something you cash in on, so I kept things low-profile.”

Dan Witz

The inspiration for his first street art series stemmed from Dan Witz’s recognition that New York’s art scene was tightly clustered within SoHo. Motivated by this, he sought to expand art’s reach beyond this exclusive enclave and into the broader public space.

“I used to think that art was all about the money, the value, like a big corporate branding thing for artists. That’s probably why it felt so sidelined, stuck in places like SoHo—because it seemed like nobody really cared or wanted to dig deeper. So, I started wondering, what if art wasn’t something you could buy? What if it wasn’t for sale? Would that shift how people see art altogether? Back then, people thought I was nuts, asking me how I’d make a living, who’d even see my work, or what’s the point. But that idea really grabbed me, and I’ve stuck with it my whole career, that’s like 40 years now. Imagine art not as a brand or something to be auctioned off, but just as something people come across. What if it was anonymous? Not all tangled up in being elitist or overly intellectual? What if it was something simple, like a little bird or a skateboarder—something even kids could connect with? That’s been my approach for my entire career.”

Dan Witz

In addition to people thinking he was crazy, there were art professionals, including gallerists who showcased his fine art canvases, who were quite dismissive of street art.

“I’d have my work in galleries from time to time, and when it came to my street art, the reactions were pretty funny. They’d be so dismissive, and I’m there thinking, ‘Seriously? You don’t see the value in this?’ It’s because they’re all about that high art, traditional aesthetics. They’d look at me and be like ‘It’s really sad you’re doing that.’ Just couldn’t believe their reactions.”

Dan Witz

No one, whether they were just walking by or deeply entrenched in the art world, really grasped what Dan Witz was up to. Despite this, he continued to spread his hummingbird paintings throughout New York City, alongside tags, throw-ups, and OG graffiti lettering. At that time, the underground scene was tight-knit and small: the legends of NYC graffiti all came to know him and, over time, grew to appreciate the work he was doing in their shared playground.

“The main thing was not to cover anyone else’s work—that was the golden rule. Once they saw I respected that, we were all good. I think they could tell I was a fan, not out to exploit what they were doing or anything. Just a fan, doing my own thing. And these hummingbirds I painted were tiny, not stepping on anyone’s toes. They’re pretty hard to hate, being so pretty and all, unless you’re one of those conceptual artists who thinks art shouldn’t be appealing, or that it’s just kitsch. But, you know, punk had its kitsch side too, kind of a ‘screw you, I’m doing kitsch now.’ And since then, there’s been a lot more room for kitsch in street art. It’s like a slap in the face to the high art scene and its super strict rules on what’s aesthetic.”

Dan Witz

Dan Witz’s street art has never been merely aesthetics, though. Each of his projects is layered, carrying its own unique underlying message.

“I start off with a certain message in mind for each project. But by the time it’s all finished, it’s morphed into something totally different. I keep an open mind and let the process evolve. Often, there’s this happy accident that happens because I’m not scared of messing up. So, I mess up, give it another go, and each time I mess up a little less badly. The initial concept usually ends up changing a lot by the end. I’m drawn to projects with a message; it kinda fuels me, helps me push through the tough parts of creating something, because there’s a lot of trial and error, a lot of starting over. Having that strong theme to follow is like a light guiding me through. And if there’s one thread running through my work, it’s this idea that there are all these weird, hidden things happening just below the surface of everyday life.”

Dan Witz

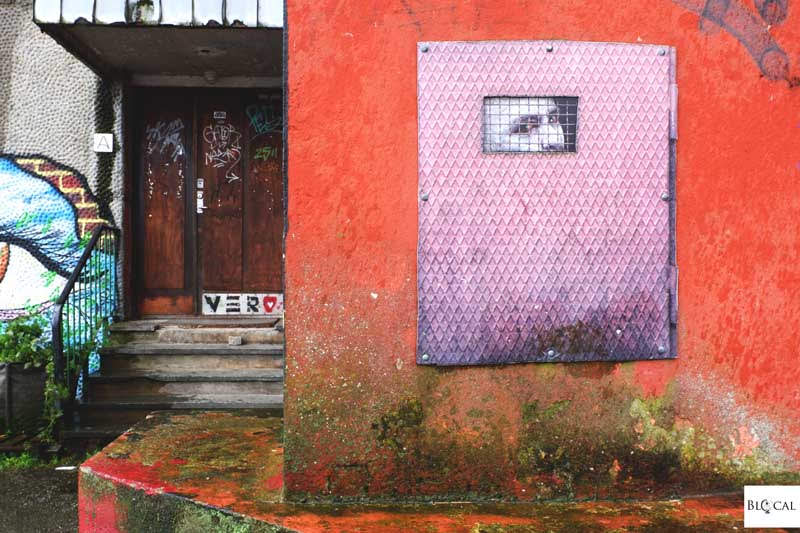

Underneath the surface is where many of Dan Witz’s characters seem to exist: throughout the years, he has developed several series portraying individuals caught behind bars. This theme began with his “Ugly New Buildings” project in 2008, a reaction to the destruction of his Brooklyn neighborhood for luxury condos, powerfully expressing the sense of entrapment and yearning for freedom that comes with gentrification. He then continued this theme with “What The F%$#@ (WTF)” series in 2010, featuring hyper-realistic human figures confined behind bars, subtly integrated into urban environments to startle passersby and spark wonder in the mundane.

Expanding on this theme, in 2023 Dan Witz took his #isitsafe project to Civitacampomarano in Italy, a village renowned for the CVTà Street Fest. That’s precisely where we met. (and, after the privilege of closely observing him working for a week, I had the opportunity to record this interview).

- Read also: “Behind the Scenes of CVTà Street Fest 2023“

Dan Witz’s #isitsafe project, initiated in response to the Trump administration’s policy of detaining immigrants in the U.S. who lacked proper documentation, is about families torn apart. Authorities would separate children from their parents at the border as a deterrent to immigration. Thousands of children, some as young as three years old, were placed in detention centers.

“It was heartbreaking. I built on that, and using the theme #isitsafe, it felt like the injustices were just piling up. It kept getting more relevant. There’s a bunch of reasons to feel ‘not safe’ in America. Obviously, there’s COVID, and then the mass shootings – it’s like there’s one every couple of days. So, the stuff I did around the immigration issue, it kinda naturally extended to the crisis with mass shootings. Then, finding out I was headed to Italy, I remembered how hard COVID hit Italy, just as bad as it did New York where I live. That clicked for me. Plus, there’s this ongoing immigration crisis here too. So, it felt really fitting to bring the series over here.”

Dan Witz

Last summer, for the CVTà Street Fest, Dan Witz also crafted a mural named “Peace Out,” which features the depiction of memorial lanterns.

“This whole thing started when I lost my father-in-law to COVID, and it hit me really hard. I tend to work through what I’m feeling by putting it into my art. Like after 9/11, I made a series of memorials. So, I dove into this project, but it was a long journey, took years to figure out exactly how to do the memorials right, how to paint them, how to really capture what I wanted. By the time I got it right, people weren’t talking much about COVID anymore. That was the spark for me, but then, it seems like every time I turn around, there’s news about kids getting shot at schools, and it just drives me nuts. I guess in a way, these pieces have become a memorial for all those we’ve lost too soon. It’s how I deal with things, how I process.”

Dan Witz

In the words of Dan Witz, art becomes a tool for coping with the uncontrollable and often harsh realities of the world.

“There’s a bunch of shit in the world that you can’t do anything about…you are powerless, you can’t affect anything, and I don’t think my work affects anything, but as long as I make a gesture towards it I feel like I’ve tried something.”

Dan WItz

This admission doesn’t come from a place of defeat but rather an acknowledgment of art’s role in personal healing and societal reflection. Despite his skepticism about the immediate impact of his projects, such as the “Peace Out” lanterns, it’s the act of creation itself that provides him a way to alleviate some of modern life’s anxieties.

While highlighting the importance of taking even small actions to contribute to a larger change, Dan Witz brought up his engagement with PETA (People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals), an organization dedicated to animal rights and promoting vegan lifestyles. (Funnily enough, one of the highlights of our relationship for me was bonding over a week of vegan adventures at the festival) By discussing the idea of the tipping point, he emphasizes that individual actions, however small they may seem, can cumulatively lead to significant societal transformations. His collaboration with PETA, among other efforts, exemplifies how sustained advocacy and artistic expression can enhance awareness and gradually alter public attitudes. His work reaffirms that art transcends mere expression; it acts as a lever for advancement, compelling us to play our part in reaching the tipping point for meaningful change.