The Appartengo Public Art Festival invited me to follow the work in progress of Argentinian street artist Milu Correch, known for painting non-stereotypical, narrative-based murals all around the world.

“The thing you have to understand about the evil eye,” said the zealous, nostalgic-looking expert of Anthropology and Ethnography Rocco De Rosa while leading us through his collection of various ancient agricultural tools, “is that you need a home protector to keep it outside your doorstep. Here they are. They come in different designs, usually inspired by male genitalia.”

Milu Correch began her own research into local stories from Stigliano’s evocative History Museum of Rural Life (Museo di Storia e Civiltà Contadina). She took photos, she asked questions, and she listened to the stories of the infamous witches from Basilicata, which have inspired even the Grimm brothers.

In recent years, witchcraft has been the main thing on Milu Correch’s mind. It gives her the perfect occasion to explore stories that are in balance between this world and another still hidden, suggesting an imagery that is filled with mystery and unanswered questions. Moreover, witches symbolize a political ideal; they represent an alternative power that has been brutally targeted from the late 16th to early 18th century in Western Europe, when over 40,000 women were killed.

What I like about witchcraft is the fact that these women held the power in their hands. Their knowledge wasn’t something outside themselves, but simply the understanding of nature. They needed no priests or doctors to rely on, rather they were self-sufficient in taking care of the community. That’s why they burnt them, to steal this power away from women and centralize it into two institutions completely ruled by men, the Church and the State.

Milu Correch

Somehow, this alternative knowledge survived to the present time and on our second day in Stigliano we visited a local woman who is an expert in white magic and pranotherapy. Over a cup of chamomile, she kept fueling Milu Correch’s inspiration with her personal stories.

I like to make women’s power shine through the stories of local witches. I also use these subjects to change the way women’s bodies are represented in art; not anymore as objects defined by the male gaze, harmlessly laying down in a passive pose, but as protagonists with the active power of changing reality through their spells.

Milu Correch

In representing figures empowered by their own story and subjectivity, Milu Correch blurs the border between male and female bodies, inflecting a new combination of different characteristics and attributes. This ambiguity is common in the representation of witches through centuries; in Rocco De Rosa’s collection we found images of the “Masciara,” a witch from Southern Italy often represented as a bearded woman. Moreover, painting outside the gender dichotomy brings to the wall a series of conflicting elements that make the image unsettling, which is just how Milu Correch likes it.

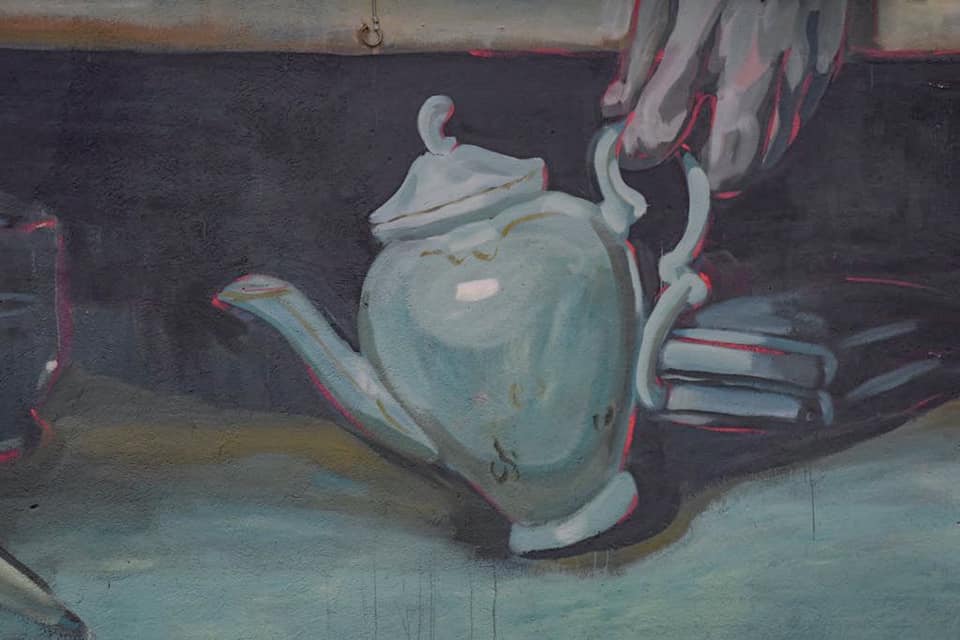

When the rain came on our third day, Milu sheltered at home and began working on the concept of her wall for the Appartengo Festival. She gathered various objects from the kitchen and arranged them on the floor beneath the bed. She wrapped a bed sheet over my head, set the perfect lighting, and, lying on the floor, gave me some basic directions while shooting photos, which became the starting point of her sketch.

After one more day of drawing, she could supersize the sketch, taking it from her notebook to the wall with the help of a grid, a basic technique that she learned while watching her friends paint in the streets of Buenos Aires.

With no academic background, Milu Correch’s art is strongly influenced by the way street art is done in Argentina, where there are no street art festivals and only a few commissioned murals, while the majority of street art is spontaneous and most welcome. In Buenos Aires, it’s common to see groups of friends having fun painting together, making the most of the tools they have, because there’s no sponsor or institution providing spray paint, scaffolding, lifts, or any other fancy tool.

There’s a saying in Argentina – ‘es lo que hay,’ (it is what you have) – for all the times we have to come up with creative solutions to make up for what we don’t have. My painting process comes from this way of thinking. I only use rollers, brushes and water paint, because these basic tools are widely available in Argentina. I could never have a projector at the core of my process, because imagine what happens if you leave a beamer in the middle of a street in Buenos Aires. This kind of ‘street experience’ is not only about painting techniques, but also finding out where the closest toilet is, or keeping an eye on each other’s stuff while painting. The streets of Buenos Aires have been my school, and obviously my art is influenced by this way of painting.

Milu Correch

In keeping with the rich tradition of Latin American muralism, Milu Correch paints large-scale murals with strong narratives. Dating back to the beginning of the 20th century (and so long before the outbreak of street art as a global phenomenon), Latin-American muralism originated as a social and political tool to express national pride and broadcast identitary messages after the independence from European colonizers. Therefore, the stories painted on walls all across the Latin-American continent had to be easily readable for a widely illiterate population in order to convey the sovereign values.

Milu Correch, instead, paints stories that are ambiguous and full of mystery. She refuses to arrogate to herself the right to state the truth or to communicate a message in a linear way. Rather, she prefers to raise questions and leave them unanswered, thus opening her imagery through a curiosity that is impossible to fully satisfy.

I paint the unspoken, what it’s impossible to pin down because it’s ambivalent, on the border. I always ask myself: would this image work with a Coca-Cola logo on it? If a commercial logo would make no difference, it means that my image is patinated, self-explanatory and obvious. And that’s not what I want.

Milu Correch

Milu Correch’s murals are not readable in an analytical way. She relies on the viewers to actively connect the dots. Away from cliches, stereotypes, and legible signs, her murals harbor limits and contradictions, engaging the viewers in bringing their personal experience to the wall.

I like to provide the ingredients and then leave to the viewer the power of making a dish with them, to come up with their own interpretations. This way the artwork isn’t only mine, it’s also theirs.

Milu Correch

This perceptive mode of engaging the imagery, which comes before any rational “knowing” or “‘understanding,” is also suggested by Milu Correch’s use of colors. Like music, her palette, which is never saturated, suggests an emotion or a state of mind. It originates spontaneously, because colors are mixed directly on the wall through a messy brush stroke that, itself, intensifies the obscurity.

The colors I prepare beforehands are just a starting point. To some extent, I like my practice to be out of my control. I like when new colors arise from the wall, or when the mural shows a distinctive character, which I hadn’t anticipated in the sketch. I don’t wanna paint like a robot, perfectly executing a sketch like if I were a machine. I always leave some space for the unexpected.

Milu Correch

On my trip back home, I stopped in Montalbano Jonico to say goodbye to Milu. We had a walk and she shared with me her enthusiasm for the colors of the historic center and the lunar landscape of the badlands surrounding Montalbano Jonico, as well as her apprehension for being the first muralist to work in the village.

It’s definitely a challenge, because when you paint in a village you have all eyes on you. It’s nothing like painting in a big city like Buenos Aires. Moreover, this is the first time that the Appartengo festival comes to Montalbano Jonico. People might be used to murals in Stigliano, where the festival began in 2017, but here I’m the first one and that’s a huge responsibility.

Milu Correch

A few days later, her concern turned out to be unjustified when Montalbano Jonico’s residents first met their “Masciara.” Drawing on a popular tradition widespread in Southern Italy and with very ancient roots, Milu Correch represented the local archetype of a lady with both medicinal and magical powers in the act of performing a ritual to remove the evil eye.

A magical knowledge that is still contemporary in Basilicata, it is the idea of women as a source of evil fostered by the Christian Church. Women that resisted the male social order by using powerful spells to make men act against their will, thus influencing a male-dominated world through their magical powers. Women suspended between mythology and history, women who are likely to end up in one of the powerful murals that Milu Correch paints all around the world.